Many teachers report that recent attention to evidence-based phonics instruction has helped them better understand the essential role of word decoding and encoding in literacy development. Evidence based practice is key to creating instruction for word decoding as well as guidance for teaching additional elements that students require to be successful. As teachers who already do great work in schools know, learning to be literate is complex, there is not one simple story or solution for reaching all learners. But research and years of experience tell us there are four dimensions that are equally essential when it comes to literacy instruction.

Becoming Literate Means Learning to Decode at Multiple Levels

Languages are systems through which meaning is organized. Literacy is the ability to understand how meaning is represented through decoding and encoding of writing and signs in texts. Teaching foundational skills for the decoding and encoding of words has gotten the most attention in the initial science of reading debates. In addition, unlocking language structures also includes teaching students to unpack sentences – such as how the grammar functions. Meaning is also built into the organization of whole text – be it a paragraph or a book. Teaching codes recognizes that learners draw on existing language knowledge as they learn to unpack school texts.

Reading and Writing with Purpose Enables Deep Comprehension

Literacy is something we “do” for a purpose. Teachers in purposeful literacy classrooms are intentional about text choice. They use talk to engage learners to think about personal, academic, or social reasons for reading a particular text or text set. These are classrooms where talk is thinking. Analytic talk invites thinking before reading/writing and while interacting around text. Analytic talk opens possibilities for stretching vocabulary – building word wealth — a key predictor of school success. Including purpose in lessons links strategic reasoning/thinking to deeper comprehension — comprehension strategies are not ends in themselves but tools for obtaining meaning.

Competence and Confidence Are Mutually Reinforcing and Vital for Readers and Writers

Measures of student learning are heavily focused on cognitive growth – the mind. Neurological research reminds us that the mind is interconnected with the experiences of the body. Peer reviewed studies from areas such as history, sociology, and anthropology tell us that the relationship between cognitive and social/cultural factors shapes the brain. Excellent literacy teachers trust that all learners are capable through their unique abilities, languages, family stories, and life experiences that contribute to their learning. This asset perspective sends a message of competence which builds confidence. Instead of “watering down” or simplifying curriculum with the goal of fixing a deficiency, excellent teachers aim to reach all readers by “watering up” with high expectations/high scaffolding inclusive instruction.

Engaging Critically with Texts Is Essential and Transformational

Critical engagement demands higher cognitive reasoning and is not always visible in assessments and standards. Critical engagement involves two areas: critical reading, the analysis and evaluation of text, and critical literacy, which focuses on interacting with texts for transformative purposes and using literacy for action. Critical reading and critical literacy can intersect by bringing criticality to current practices such as encouraging readers to construct meaning and transform thinking. Students can be challenged to make text connections – based in their own experiences –while also stretching them to engage in close reading – drawing on evidence in the text itself. Adapting current curriculum may involve swapping out existing literature and replacing it with texts students relate to. When readers and writers see relevance they rise up and succeed.

An Integrated Framework for Reading Is Needed

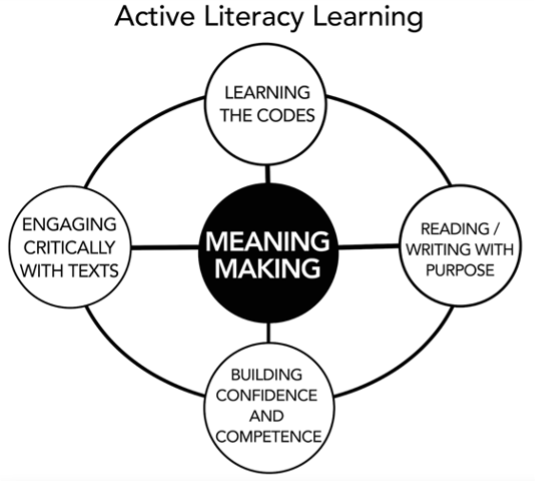

My co-author and I developed The Active Literacy Learning (ALL) framework to provide a lens for examining these multiple factors necessary for reading development. The four-dimensional framework below addresses complexity as it keeps meaning making (the point of literacy) central – each dimension is equally important yet interrelated. It is a dynamic model derived from the field of literacy education where all areas are equal in importance and interdependent in teaching all learners.

Are there aspects of this you want to dig into further?

Let’s continue the conversation on October 24 at Lesley University or virtually, as I open the Reaching All Learners speaker series. We will talk more about bringing this to life in your classroom.

References:

Brisk, M. E. (2014). Engaging students in academic literacies: Genre-based pedagogy for K-5 classrooms. Routledge.

Compton‐Lilly, C. F., Mitra, A., Guay, M., & Spence, L. K. (2020). A confluence of complexity: Intersections among reading theory, neuroscience, and observations of young readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S185-S195.

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press.